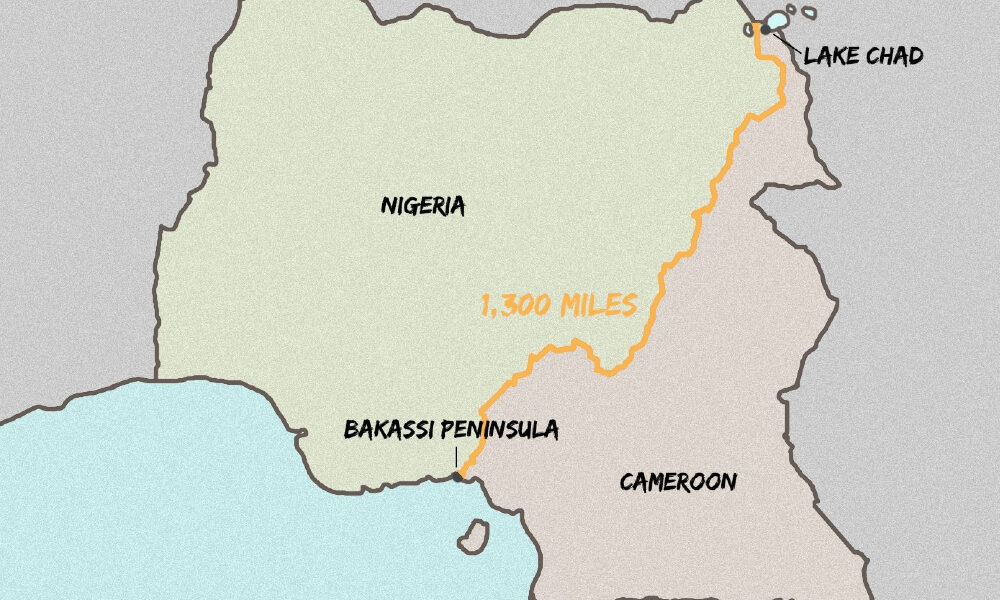

Nigeria and Cameroon share a border of approximately 2,062 kilometres, stretching from Lake Chad in the north to the Gulf of Guinea in the south. The current boundary owes its origins to colonial treaties signed between Britain and Germany in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly the Anglo-German Agreement of 1913, which sought to define the frontier between British Nigeria and German Kamerun.

After the First World War, German Kamerun was divided between France and Britain under League of Nations mandates. British-administered Southern Cameroons later voted in a 1961 plebiscite to join the Republic of Cameroon, while Northern Cameroons joined Nigeria. Both countries thus inherited boundaries drawn by European powers that often ignored local ethnic and economic realities.

Despite post-independence recognition of these colonial borders, ambiguities persisted, particularly in the Bakassi Peninsula and areas surrounding Lake Chad. The Bakassi region, a low-lying mangrove area rich in fishing resources and potential oil reserves, became a centre of contestation, with both Nigeria and Cameroon asserting sovereignty.

Key Events and Influential Figures

Early Tensions and Armed Clashes

Minor disputes along the border date to the early 1970s, but the situation escalated in May 1981, when Nigerian and Cameroonian patrols clashed, leaving casualties on both sides. Diplomatic efforts led by the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) de-escalated the conflict, but tensions persisted.

EXPLORE NOW: Democratic Nigeria

In the 1990s, incidents multiplied, particularly after February 1994, when Nigerian troops occupied parts of Bakassi to “protect” local inhabitants who identified as Nigerians. Cameroon viewed this as a violation of sovereignty and took the matter to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in March 1994.

The International Court of Justice and the Greentree Agreement

The ICJ’s 2002 judgment, based largely on colonial treaties such as the Anglo-German Agreement (1913) and subsequent protocols awarded sovereignty over Bakassi to Cameroon. Nigeria’s claims, rooted in effective occupation and local allegiance, were rejected on legal grounds.

Presidents Olusegun Obasanjo of Nigeria and Paul Biya of Cameroon accepted the ruling, seeking to avoid renewed hostilities. In June 2006, under United Nations supervision, both nations signed the Greentree Agreement in New York, setting a timetable for Nigeria’s withdrawal.

By August 2008, Nigerian troops and administration had fully withdrawn, completing the transfer of authority. The Cameroon–Nigeria Mixed Commission (CNMC), chaired by the United Nations, was established to oversee demarcation, population concerns, and ongoing cooperation.

Legal and Diplomatic Framework

The ICJ ruling rested on multiple treaties, including:

- The Anglo-German Treaty of 11 March 1913, which defined maritime and land boundaries between Nigeria and Kamerun.

- The Maroua Declaration of 1975, signed by General Yakubu Gowon (Nigeria) and President Ahmadou Ahidjo (Cameroon), which refined maritime limits.

Although Nigeria argued that the Maroua Declaration was never ratified, the ICJ considered it binding under international law. The Court further emphasised that African states had pledged to respect colonial boundaries under the 1964 Cairo Declaration of the OAU.

Following the ruling, some Nigerian legislators and civil society groups opposed the handover, calling it unconstitutional. Nevertheless, the government cited Article 94 of the UN Charter, which compels compliance with ICJ decisions.

To maintain peace, the CNMC facilitated demarcation, security patrols, and humanitarian measures for affected residents.

EXPLORE: Nigerian Civil War

Economic and Social Consequences

Resource Stakes

The Bakassi Peninsula is endowed with abundant fish stocks, oil, and natural gas deposits, which made the dispute economically significant. Nigerian scholars such as Hart Akie Opuene note that hydrocarbon exploration heightened competition between both states, particularly after offshore discoveries in the 1980s.

Control of maritime boundaries directly affected fishing rights, trade routes, and oil concessions. For decades, local Nigerian fishermen operated freely in Bakassi waters under Nigerian administration; after the cession, many faced restrictions, taxation, and displacement.

Humanitarian and Social Impacts

Following the handover, tens of thousands of Nigerians were left on Cameroonian territory. The Greentree Agreement granted them options: to retain Nigerian nationality while remaining in Cameroon or to relocate. Many opted to move to Cross River and Akwa Ibom States, where resettlement camps, such as Dayspring Island, were established.

The transfer disrupted livelihoods and community ties. Some returnees complained of inadequate compensation and poor living conditions. Meanwhile, Cameroonian authorities integrated remaining residents into their administrative framework, extending local governance and social services.

Trade across the southern border also declined during tense periods, particularly between Calabar and Idabato, affecting local economies dependent on fishing and informal commerce.

Colonial Influence

The Nigeria–Cameroon boundary reflects broader patterns of colonial cartography in Africa, where European powers prioritised strategic and economic interests over indigenous realities.

The Anglo-German Agreement (1913) was central to later legal arguments. It demarcated boundaries using coordinates that often ignored natural features and settlements. Subsequent colonial adjustments, such as the Yaoundé II Declaration (1971) and Maroua Declaration (1975), sought to clarify ambiguities but introduced new disputes, particularly in maritime zones.

Because colonial surveys were imprecise in swampy or mangrove areas, post-independence governments inherited vague and overlapping claims. These inconsistencies made it difficult to separate historical occupation from formal sovereignty, a challenge repeated in other African borders, such as the Ethiopia–Eritrea and Sudan–South Sudan disputes.

Legacy Today

The peaceful conclusion of the Bakassi dispute is frequently cited as a model for international conflict resolution in Africa. Despite initial opposition, Nigeria’s compliance demonstrated a commitment to international law and regional stability.

The Cameroon–Nigeria Mixed Commission, with UN backing, continues to supervise the demarcation of over 2,000 kilometres of boundary and promote cooperation. Occasional local clashes persist, especially in the Lake Chad region, where insecurity and climate stress compound border ambiguity.

The episode reshaped Nigeria’s diplomatic image. It reaffirmed that border disputes in Africa can be resolved through legal means rather than warfare. However, it also exposed weaknesses in Nigeria’s border administration and the need for stronger policies to protect affected citizens.

Conclusion

The Nigeria–Cameroon border dispute, particularly over the Bakassi Peninsula, reflects the enduring legacy of colonial boundaries and the intersection of law, resources, and identity. From the 1981 skirmishes to the 2008 handover, the conflict moved from confrontation to diplomacy, culminating in a rare example of peaceful territorial transfer in Africa.

While the dispute is formally settled, its human and economic consequences endure. The story of Bakassi continues to shape Nigeria’s approach to international law, maritime governance, and the protection of border populations.

Author’s Note

This article presents an overview of the Nigeria–Cameroon border disputes based solely on verified academic and institutional sources. It highlights how colonial boundaries, economic interests, and legal rulings shaped relations between both nations. The peaceful resolution of the Bakassi question remains a landmark in African international diplomacy and a lesson in balancing sovereignty with justice.

References

- African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD). Implications of the Bakassi Conflict Resolution for Cameroon and Nigeria. 2011.

- United Nations Office for West Africa and the Sahel (UNOWAS). Cameroon–Nigeria Mixed Commission Reports. UNOWAS Publications, 2020–2024.

- Opuene, Hart Akie. “Resource Conflicts and Nigeria’s Border Politics.” African Journal of Political and International Relations, Vol. 5 (3), 2021.