Introduction

The Nigerian Police Force (NPF) is one of the country’s most enduring institutions, with origins dating back to the colonial era. From its beginnings as a small consular guard in Lagos to its current role as a nationwide security institution, the NPF’s evolution reflects Nigeria’s political, social, and governance struggles. Understanding its history highlights the challenges of policing in a diverse and complex society.

Early Policing Traditions

Before colonial rule, policing in present-day Nigeria was carried out through indigenous systems. In Yoruba kingdoms, palace guards enforced traditional laws; in Hausa-Fulani emirates, the Dogarai maintained order under the authority of emirs; and among Igbo communities, age-grade associations enforced communal rules. These decentralised systems relied heavily on community trust and accountability.

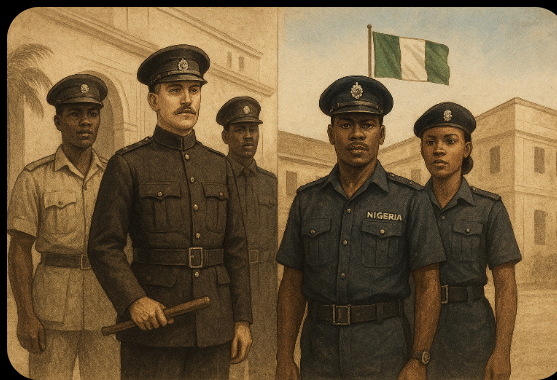

Colonial Beginnings (1861–1930)

Formal colonial policing started in 1861 when Lagos became a British colony. That year, a small Consular Guard of 30 men was established to protect colonial officials and enforce order. By 1879, the Hausa Constabulary was created, largely composed of recruits from Northern Nigeria, who were considered more reliable by the British due to their distance from Lagos politics.

In 1896, the Lagos Police Force was formed, while other regional constabularies emerged in the Oil Rivers Protectorate (later Southern Nigeria) and the Northern Protectorate. These units were heavily militarised, focusing more on safeguarding colonial interests, collecting taxes, and suppressing resistance than protecting local communities.

The amalgamation of the Northern and Southern protectorates in 1914 did not immediately unify policing, as forces remained fragmented across regions. It was not until 1930 that the colonial administration merged the regional forces into a single Nigeria Police Force, headquartered in Lagos. This centralised force inherited its militarised, authoritarian structure, prioritising control over public service.

The Police in Post-Independence Nigeria (1960–1966)

At independence in 1960, the NPF became a national institution under Nigerian leadership. However, it continued to operate under colonial legacies of centralisation and paramilitary discipline. During the First Republic, policing was marked by political interference, electoral violence, and ethnic rivalries.

Alongside the federal police, regional governments maintained local police forces. These regional forces were often accused of political bias and intimidation, fuelling tensions. Following the January 1966 military coup, the federal government abolished regional police, consolidating all policing powers under the central command to curb political misuse.

READ MORE: Ancient & Pre-Colonial Nigeria

Policing under Military Rule (1966–1999)

Military governments ruled Nigeria for most of the period between 1966 and 1999, leaving deep imprints on the NPF.

Civil War (1967–1970)

During the Nigerian Civil War, the police supported military campaigns through intelligence gathering and maintaining order in contested regions. This period intensified the force’s militarisation, reducing its role in civilian law enforcement.

Post-War Expansion

The 1970s oil boom brought rapid urbanisation, crime growth, and increased demand for policing. The Police Act of 1979 reaffirmed the NPF as the sole national police body. However, corruption, inadequate funding, and poor training limited effectiveness.

By the 1980s and 1990s, economic decline and political repression fuelled rising crime rates. The police were frequently accused of human rights abuses, extortion, and inefficiency. Public trust declined, and the police became a symbol of Nigeria’s governance crisis.

The Police in the Fourth Republic (1999–Present)

Democratic transition in 1999 brought new hopes for reform. Civil society organisations, the media, and international partners pushed for modernisation, professionalism, and respect for human rights.

Reform Efforts

The 2000s saw attempts at reform, including community policing initiatives and welfare improvements. Units such as the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) worked with the police in tackling corruption and fraud. Nevertheless, structural issues persisted: corruption remained widespread, funding inadequate, and accountability mechanisms weak.

SARS and Public Backlash

One of the most controversial units, the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS), became notorious for brutality, extrajudicial killings, and extortion. Long-standing grievances erupted in October 2020, when youth-led #EndSARS protests spread nationwide. The government announced the disbandment of SARS, but calls for comprehensive reform of the NPF intensified.

Structure of the Nigerian Police Force

The NPF is governed by the Police Act, 2020, which defines its core functions:

- Prevention and detection of crime

- Protection of life and property

- Enforcement of laws and regulations

- Prosecution of offenders

The Inspector-General of Police (IGP), appointed by the President, heads the force. It is organised into 36 State Commands and the Federal Capital Territory, grouped into 12 zonal commands, and further divided into areas, divisions, and stations.

Notable Figures in Police Leadership

- Louis Orok Edet (1964–1966): First Nigerian Inspector-General, who managed the force during the early years of independence.

- Mike Okiro (2007–2009): Introduced community policing reforms.

- Mohammed Adamu (2019–2021): Inspector-General during the #EndSARS protests.

- Usman Alkali Baba (2021–2023): Oversaw reforms following widespread demands for accountability.

Why the History of the NPF Matters

The NPF’s history demonstrates how colonial legacies, authoritarian rule, and governance challenges have shaped policing in Nigeria.

- Colonial Legacy: The force’s centralised, militarised character stems from British rule.

- Democratic Struggles: Effective policing in a multi-ethnic democracy requires impartiality, accountability, and human rights compliance.

- Public Trust: Historical abuses have eroded trust, making reform a national priority.

Conclusion

The Nigerian Police Force has evolved from a colonial paramilitary unit into a complex national institution responsible for protecting over 200 million citizens. Its trajectory mirrors Nigeria’s broader political and governance challenges, from colonialism to military rule and democracy.

While reforms such as the Police Act 2020 mark progress, challenges of corruption, inadequate resources, and strained community relations persist. For Nigeria’s democracy to thrive, the NPF must continue its transformation into a transparent, accountable, and community-focused institution.

Author’s Note

This article traces the Nigerian Police Force’s evolution from colonial origins to present reforms, highlighting how historical legacies, governance challenges, and public resistance have shaped its development. It emphasises the force’s dual struggle with maintaining order and earning public trust, underscoring the urgent need for ongoing reforms.

References

- Tamuno, T. N. (1970). The Police in Modern Nigeria, 1861–1965. Ibadan University Press.

- Alemika, E. E. O. (1993). Colonialism, State and Policing in Nigeria. Crime, Law and Social Change, 20(3), 187–219.

- Hills, A. (2008). The Dialectic of Police Reform in Nigeria. Journal of Modern African Studies, 46(2), 215–234.