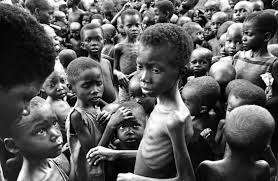

The image of a starving Biafran child in 1968, ribs protruding and eyes hauntingly large, became one of the most recognisable photographs of the twentieth century. Circulating across newspapers and television screens from London to Los Angeles, it transformed a distant political conflict into a global moral emergency. While the Nigerian Civil War was already among Africa’s bloodiest conflicts, these photographs brought the suffering of ordinary civilians to the forefront of international attention.

Nigeria’s Fracture and the Secession of Biafra

Nigeria achieved independence from Britain in 1960, inheriting a state of great ethnic and regional diversity. Tensions deepened following a series of coups in 1966 and violent anti-Igbo pogroms in northern Nigeria. Amid this turmoil, Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu declared the independence of the Eastern Region as the Republic of Biafra on 30 May 1967.

The Nigerian federal government, under General Yakubu Gowon, rejected secession and launched a military campaign to preserve national unity. What was initially described as a short “police action” escalated into a full-scale civil war that would last until January 1970.

Blockade and Famine

A decisive factor in the war was the federal government’s blockade of Biafra. By mid-1968, land and sea routes into the enclave were sealed, preventing food, medicine, and fuel from reaching civilians. Malnutrition spread rapidly, with children the most vulnerable.

Kwashiorkor, a severe form of protein deficiency, became the defining image of the conflict. Children with swollen stomachs, brittle hair, and hollow eyes appeared in reports worldwide. Estimates of famine-related deaths range from 500,000 to 2 million, though precise numbers remain debated.

Critics argued that starvation was used as a deliberate weapon of war. Whatever the intention, the humanitarian consequences were catastrophic.

READ MORE: Ancient & Pre-Colonial Nigeria

The Camera as Witness

The suffering in Biafra might have remained a distant tragedy were it not for the work of photojournalists and reporters. Don McCullin, the British photographer, travelled to Biafra in 1968 and produced stark images of emaciated children and families. Alongside other photographers such as Gilles Caron, McCullin’s work ensured that the famine dominated international headlines.

These photographs forced the global public to confront the human cost of war. They became central to the visual language of humanitarian crises, shaping how the world understood famine and civilian suffering in conflict zones.

The Airlift: Relief in the Shadows

In response to international outrage, relief efforts expanded. The most dramatic was the nightly airlift into Uli airstrip, nicknamed “Annabelle.” Pilots flew without lights to avoid detection, bringing powdered milk, dried fish, beans, and medical supplies. A secondary strip at Uga was also used.

Organised first by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and later by church-based groups such as Joint Church Aid, the airlift became the largest humanitarian operation of its kind since the Berlin Airlift. Although estimates of the tonnage vary, hundreds of nightly flights managed to save lives, though never enough to meet overwhelming needs.

The mission was dangerous: planes were shot at, and aid workers were killed. In June 1969, after an ICRC plane was shot down, the organisation suspended flights, leaving church groups to continue on a reduced scale.

Doctors and Humanitarian Principles

For many aid workers, Biafra was a turning point. French doctors who worked under the Red Cross, including Bernard Kouchner, became frustrated with restrictions that prevented them from speaking openly about atrocities. Their experiences in Biafra contributed directly to the founding of Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) in 1971. This marked the birth of a new humanitarian ethos: relief combined with testimony, known as témoignage.

Journalists and Witnesses

Foreign correspondents also played a key role. Frederick Forsyth, then a BBC journalist, resigned over restrictions on reporting and went on to publish The Biafra Story (1969). His account, while controversial in its advocacy, ensured that Biafra could not be ignored.

The War’s End

On 12 January 1970, Biafra’s acting leader Philip Effiong announced a ceasefire and surrender. Three days later, General Gowon declared that there was “no victor, no vanquished,” promising reconciliation.

The war ended, but famine’s legacy remained. Families carried memories of displacement, loss, and hunger. Internationally, “Biafra” became shorthand for famine itself, a term often invoked when discussing humanitarian emergencies.

Legacy

The Nigerian Civil War left deep scars, but it also reshaped global humanitarianism. The images of starving children, the boldness of airlifts, and the courage of journalists and doctors together forged a new template for international relief operations.

Biafra demonstrated both the power and the limitations of humanitarian action: it saved lives, but it could not end the war.

Author’s Note

This article is based on historical documentation and survivor testimony. The Nigerian Civil War revealed how famine, photography, and relief efforts intersected to transform humanitarian practice. The “Biafra baby” image remains controversial but undeniable in its influence, reminding the world of the urgent moral stakes of civilian suffering in war.

References

- Don McCullin, Unreasonable Behaviour: An Autobiography (London: Jonathan Cape, 1990).

- Frederick Forsyth, The Biafra Story (London: Penguin, 1969).

- Michael Draper, Shadows: Airlift to Biafra (Manchester: Hikoki Publications, 1999).